Making the Links in Family Violence Cases: Collaboration among the Family, Child Protection and Criminal Justice Systems

Chapter 5 - Coordination of court proceedings

5.1 Challenges

As noted elsewhere in this report, family members facing family violence may be involved in multiple proceedings. Due to the structure and organization of the courts, families need to navigate multiple sectors of the justice system which have different purposes, processes and timing. In addition, the relevant courts may be either provincial or superior courts and therefore funded by different government even if they are in the same jurisdiction.Footnote 218 These factors make it challenging for family members to get effective access to the justice system to resolve their issues in a meaningful fashion.

This problem is exacerbated by the high rates of self-represented litigants who do not have the assistance of someone who is legally trained, to guide them through the various proceedings and systems. For example, between 2006 and 2010, at the time of the filing of the court application, over 50% of family law litigants in Ontario were self-represented.Footnote 219

Specialized domestic violence courts or court processes

One area where there has been a significant amount of work in terms of improving the court system with respect to family violence is the introduction of specialized domestic violence courts or court processes.

In practice, the vast majority of offences related to family violence are tried in provincial court. One of the critical challenges in prosecuting domestic (spousal) violence offences relates to some victim’s concerns about providing evidence against their spouse. Victims’ reluctance may be based on a number of reasons including fear for their own or their children’s safety, love or affection for the accused, financial dependency upon the accused and concerns about the impact of criminal conviction on the accused’s employment and immigration status.

In order to improve the criminal justice system response to domestic violence, nine Canadian jurisdictions have implemented specialized domestic violence courts or court processes at the provincial court level: Manitoba (1990); Ontario (1996); Alberta (2000); the Yukon (2000); Saskatchewan (2003); New Brunswick (2007); Nunavut – Rankin Inlet (2002); Northwest Territories (2011); and Nova Scotia (2012). The specialized courts or court processes generally follow one of three models: early intervention models, some for low-risk offenders; therapeutic court models; or vigorous prosecution for severe and repeat offenders. However, regardless of the model, these courts share similar objectives, notably to provide mechanisms designed to respond to the unique nature of family or domestic violence; to facilitate intervention and prosecution of family violence; to provide support to victims; to increase offender accountability; to expedite court processing time; and to provide a focal point for programs and services for victims and offenders. Some courts also provide for specialization of police, Crown prosecutors and the judiciary.

In some domestic violence courts, for example in Saskatchewan, as well as New Brunswick, there is a dedicated judge (and in Saskatchewan, dedicated Crown prosecutors, duty counsel lawyers and probation officers)Footnote 220 assigned to the court for a period of time, which provides for consistency. In these courts all accused with charges involving domestic violence are referred to the domestic violence court by police. In other domestic violence courts, however, as well as in non-specialized criminal courts, the accused may appear before multiple judges in the course of the criminal proceeding.

A number of evaluations have been conducted of the various specialized domestic violence courts in Canada.Footnote 221 A study of the Family Violence Court in Winnipeg showed increases in victim reporting rates, conviction rates, and the proportion of convictions resulting in probation supervision, jail sentences, and court-mandated treatment for offenders following the implementation of the specialized court.Footnote 222 Moreover, the Domestic Violence Front End Pilot Project in the Manitoba provincial court won the 2006 United Nations Public Service Award for improving service delivery. Recidivism studies in Saskatchewan showed that offenders entering treatment programs prior to sentencing who completed the treatment sessions recidivated less often than those who completed post sentence or were self-referred.Footnote 223

Families affected by family violence may be impacted in a number of ways due to a lack of coordination among the various sectors of the justice system (i.e. criminal, family, and child protection). These include the following:

- Families may be required to attend multiple hearings on different days, in potentially different court locations; in some centres, the family and criminal courts are not even in the same building. These family members are required to tell their story to different courts multiple times. All of this occurs at a very stressful time in their lives.

- Because of the involvement of multiple courts, each court has only a partial view of what has occurred. As a result, decisions in each court are often made without an appreciation of the family’s full situation. This partial view is exacerbated where there is no case management system within each of the justice systems (i.e. family or criminal).

- Because judges in criminal court are often not aware of the orders made by or the evidence presented to a court hearing in a family law or child protection matter and vice versa, inconsistent orders can result. For example, a judge in criminal court may make an order for no-contact with all family members, while a family court judge may make an order for supervised access. Family members and law enforcement officials can be left confused about which order should be followed, and in some cases inconsistencies can provide an opportunity for subsequent abuse.

- Further, because there is sometimes little or no coordination in terms of how long various orders are in effect, there may be gaps in protection. For example, the conditions contained in a peace bond may expire before a civil restraining order is ordered.

- Family and child protection proceedings are sometimes delayed as a result of criminal proceedings. For example, if there has been a criminal charge, and there is also an ongoing child protection proceeding, the accused parent may be advised by counsel not to speak to anyone about the alleged incident until the trial is concluded or a guilty plea is negotiated. In 2011/2012, the median length of time taken to complete an adult criminal court case in Canada was 117 days.Footnote 224 Adult criminal court cases involving certain types of charges took longer than others to complete, such as homicide (386 days), attempted murder (259 days) and sexual assault (308 days), or where multiple charges were laid (147 days).Footnote 225 This can have serious impacts on the child protection proceeding. There are strict timelines in child protection proceedings, and in some jurisdictions there are limits to the period before which a child who has been in foster care must be returned either to the family or made a Crown ward/ward of the court. In situations where the parents have reunited and, due to the criminal proceeding, the accused does not admit that the family violence occurred, the child protection concerns will likely not have been addressed within the prescribed time limits. As a result, the child may end up being made a Crown ward/ward of the court, where otherwise it may not have been the appropriate solution.Footnote 226

- Counselling, and sometimes even negotiation, may be precluded in the family context because of no-contact provisions in a bail order.

- Family litigants may be apprehensive about addressing some issues in the family proceeding for fear of the impact on the criminal case.

- Services are associated with both the criminal and family courts, as well as child protection proceedings. A lack of coordination between these proceedings may result in a duplication of efforts, and thus inefficiencies.

- Victims can also be left confused about the different processes and protections for victims in each court system. For example, the Criminal Code sets out circumstances under which a judge may appoint a lawyer to conduct the cross-examination of a victim when the accused is self-represented.Footnote 227 The situation in family court is quite different, however. A recent Ontario study of self-represented family law litigants found that there were significant numbers of cases involving family violence where the parties were self-represented (26% males and 31% females). One of the issues highlighted by judges in this context was their discomfort with the fact that the alleged abuser was able to directly cross-examine the alleged victim.Footnote 228

- As the number of processes in which family members are involved increases, the greater the potential for increased stressors on family members. In some cases, this may create increased risk of conflict.Footnote 229

- The absence of coordination can have very concrete impacts on people’s lives outside of the court process. Where families facing issues related to family violence are also facing other social challenges, such as unemployment or precarious employment, a lack of coordination between systems, and a large number of court hearings, can have a particularly adverse socio-economic impact on family members.

The Family Justice Working Group of the Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil and Family MattersFootnote 230 has highlighted the importance of both triage – the “initial and ongoing assessment of a case to determine such matters as degree of urgency, pressing needs, and the most efficient and appropriate path to resolution”

– and referrals to appropriate services. It is noted that proper triage can reduce the possibility of both gaps and overlaps in services, and thus result in efficiencies for the justice system. An important element of the triage process is screening for safety. Better and more comprehensive training, enhanced screening, and differentiated responses in cases involving family violence are widely recommended.Footnote 231 While triage would seem to be especially relevant where families are involved with multiple sectors of the justice system, for the most part, there is no “single entry” triage system for such cases into the various sectors of the justice system. As noted elsewhere in the report, different levels of court may be involved in the different justice sector responses, and each sector may have its own form of intake process.

Case study – Integrated Domestic Violence Court, Toronto, June 2012

A litigant, having spent two years on a family law matter, was also the subject of an application for a peace bond, based on allegations by his former partner. Although the case was not transferred to the Integrated Domestic Violence (IDV) Court since the family matter was almost completed, the judge sitting at the IDV Court set the next court date for the criminal proceeding. The litigant noted that he had been unemployed until recently and that every time he came to court he had to take time off work. He complained to the judge that between the family matter and the criminal matter, it seemed as though he was “coming to court every week.”

Case study – Children's Aid Society of Huron County v R G (2003), 124 ACWS (3d) 712

R.G. and S.R.(1) have two children. In July of 2000, R.G. separated from S.R.(1) after he assaulted her. S.R.(1) was charged and later convicted of this assault and the Children’s Aid Society became involved with the family. R.G. eventually moved in with another partner. In December of 2000, a neighbour overheard R.G.’s partner abusing one of her children, S.R.(2). The child was brought to the hospital by the neighbour where a number of red welts were found on the child’s legs. As a result of those injuries, the CAS went to the mother’s home and apprehended her other child (K.R.). K.R. was found to have significant injuries to the side of his face including some bleeding in the ear area. Shortly after the children were apprehended, R.G.’s partner was charged with assaulting S.R.(2) and R.G. was charged with assaulting K.R.

R.G. denied assaulting K.R. Her evidence was that she was out shopping when the injuries occurred.

Ultimately, the partner pleaded guilty to assaulting S.R.(2). The charge against the mother regarding K.R. was withdrawn at the time of the trial in November of 2001. At that time, the mother pleaded guilty to a minor assault on S.R.(2). In the interim, however, child protection proceedings moved forward with the mother reluctant to be fully cooperative for fear that it would prejudice her in the criminal court proceedings. She made almost no progress in terms of addressing the issues that brought her children into care.

In the course of the child protection proceedings, a parental capacity assessment was ordered. At the time it was completed, the mother was still subject to outstanding criminal charges relating to the very reason that the children were apprehended. In assessing the efficacy of the assessment, Justice Glenn noted:

In these circumstances, exercising a right to remain silent ran contrary to the assessor’s need to obtain information on how the children came to be harmed. Speaking frankly, however, it could have risked having these statements introduced at the criminal trial as a confession. Dr. Walter J. Friesen, Ph.D., C. Psych., completed the parental capacity assessment of the mother and the father in March of 2001. In this assessment, the mother was strikingly defensive in her responses. She portrayed herself as an exemplary citizen, an excellent parent and a person without psychological, interpersonal or moral vulnerabilities. One will never know how different this aspect of the assessment might have been had her criminal matters already been resolved and the protection issues already determined by the court.

The fact that the society felt that she misrepresented herself to the assessor has haunted her throughout the rest of the child protection proceedings since it believed that she had poor insight into her failings as a parent. Her apparent lack of insight was one of the important basis on which the psychologist determined that her prognosis for change was poor.

In child protection proceedings, the best tack a parent can take generally involves open discussion of parenting shortcomings and co-operation with the child protection authorities. The dynamics of a criminal case, however, will sometimes dictate the opposite approach. Justice Glenn makes two suggestions for ameliorating this situation and preventing child protection proceedings from coming to a stand still during the resolution of parallel criminal charges:

First, criminal counsel must become aware of the potential cost of delay and silence in the face of companion protection proceedings. Second, all parties should explore the possibility of holding a combined settlement conference and criminal pre-trial in an effort to resolve the shared facts between each case. If the resolution of a protection issue is delayed because it is tied to a criminal charge, this issue should be flagged for the next status review proceeding and resolved as soon as possible.

Excerpted from: Joseph DiLuca, Erin Dann & Breese Davies, Best Practices Where there is Family Violence (Criminal Law Perspective) (Submitted to Justice Canada, 2012) at 31-32.

5.2 Promising practices

A number of promising practices which may assist in addressing these issues have been identified. These include variations on the “one family – one judge” concept, judicial communications and court coordination models. Annex 3, in Volume II, provides more information on evaluations related to some of these court coordination models.

5.2.1 One family – one judge

There is a spectrum of how broadly “one family – one judge” can be interpreted. It ranges from one judge for a private family law case, to one judge for all related civil cases, to one judge for all related civil and criminal cases. Each of these approaches is discussed in turn.

5.2.2 One judge for each family law case

Currently, in many family courts across the country, one family may appear before multiple judges. Where case management does not exist, in cases with continuing conflict, it would not be unusual for family members to appear before five to ten different judges on private family law matters before trial. This presents particular challenges in cases of family violence, where it is critical to ensure the protection of victims and to meet children’s best interests.

Case study – Involvement of multiple judges and sectors of the justice system

The facts of the family law case Ridehalgh v De Melo, [2012] OJ 3385 (QL) (ON SC) provide an example of how many parts of the justice system may be involved where there are allegations of family violence. The case summarized here relates to the resolution of the private family law issues between the parties – custody and access in respect of two children as well as financial issues. The facts of the case also indicate the involvement of the criminal justice as well as child protection systems.

According to the trial judge, the parents of the children had a “turbulent” relationship, and separated while living under the same roof in December 2008. In March of 2009, they physically separated after a call to the police to attend at their home. The father was charged with three counts of assault and one count of assault causing bodily harm. The father denied all allegations but eventually pled guilty to one count of assault.

Shortly after the father was charged, family law proceedings, which included competing custody claims by each parent, were also commenced. The father had no access to the first child for about four months; access was then gradually expanded, but always under the supervision of his parents. The bail conditions of the father prohibited contact with the mother. While the father was on bail, however, he and the mother did have contact and a second child was conceived.

The involvement of child protection with the parents was referenced extensively in the decision. The intersection of the child protection and criminal law system was relevant to the timing at which the father accessed services. The father testified that he had been required to participate in a men’s anti-violence program as part of his probation, as well as a substance abuse and awareness program. He admitted under cross-examination that child protection officials had previously asked him to participate in these same programs, but that he wanted to wait until the criminal proceeding was completed before doing so.

The trial judge ultimately found that the father had engaged in family violence and that his refusal to acknowledge his problems with respect to anger and domestic violence was problematic. Custody was awarded to the mother and reasonable access to the father; the court concluded that supervised access was no longer required. The parties were encouraged to reach their own agreements with respect to timesharing, but the court established a default access regime in the event that they were not able to do so.

From the perspective of case management and coordination, it is worth noting that six different judges issued orders in the family case. Three years passed between the commencement of the family law proceedings and the trial, and several temporary family law orders were issued in the interim.

Some of the challenges when there are multiple judges are as follows:

- There may be delay as no one judge is monitoring the progress of the case and ensuring that the parties complete the steps in the process in a timely way. It is often the parties who decide how frequently they will come to court and the rate at which matters will proceed.

- Each judge may take a different approach to similar issues, which can lead to inconsistency. For example, one judge may treat breaches of an order very seriously, and impose sanctions, while another judge hearing a motion with respect to a further breach, may take a different approach. This lack of consistency can create risks to safety and leave family members confused and uncertain about what to expect.

- This lack of consistency can also encourage a proliferation of motions as litigants have little to lose making the same arguments before a different judge with the hope of getting a different result. Further, without a judge monitoring the overall number of applications, their frequency, or necessity, vexatious litigation can result in perpetrators using the legal system to continue abuse of the victim. This has been referred to as “paper abuse” or “procedural stalking.”Footnote 232

- All of the above can drag out the family law case and the conflict and can result in additional costs both to litigants, as well as to the justice system as a whole.Footnote 233 As just one example, each time the case comes before a new judge, he or she must learn the case anew.

Coordination among different sectors of the justice system is certainly more challenging and complex in this context. Commentators have suggested that the family justice process in Canada ideally requires a system whereby one judge manages and hears all pre-trial appearances while another judge presides over the trial and hears all post-disposition matters.Footnote 234 It is argued that this is consistent with the modern role of judges in both family cases generally, as well as in specialized domestic violence courts, where judges go beyond their role as neutral decision-makers, and take a problem-solving approach to the family.Footnote 235 The emphasis on consistent post-disposition adjudication is also argued to be critical. Because of the nature of family law proceedings, there is often no finality to the issues. As a result, even if a matter is ultimately resolved by way of trial, there may still be a need for the family to come back to court on more than one occasion due to changed circumstances.

Some of the advantages of the “one family – one judge” model in the family violence context are that the judge:Footnote 236

- Can take overall control of the management of the case and ensure that the number of proceedings are appropriate, thus minimizing the potential for “paper abuse.”

- Can monitor over time the actions of parents and act rapidly to hold parents accountable when court orders are breached. In the family violence context, this is particularly important with respect to provisions related to contact.

- Can gain important insights about the particular programs and services to which the family should be referred. Because the judge would have contact with the same family over a period of time, he or she may become familiar with the family dynamics and patterns, which can inform decisions about the types of solutions that may be appropriate for the family.

- Can consistently emphasize the need for appropriate behaviours, such as putting the interests of the child first, and discouraging abusive behaviours. Skilled engagement by the judge with the family members can have the impact of motivating behavioural change.Footnote 237 This is over and above the ability of judges to issue orders.

There are good examples of the “one family – one judge” approach being used in Canada. For example, the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench has a case management system, which is applicable to family law cases. Upon application by one of the parties, a single judge may be designated to hear all applications related to an action other than the trial. To further enhance case management, the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta is currently piloting a case management counsel project. Case management counsel, in Edmonton and Calgary, provide support to the parties and to the judge, as appropriate. The Case Management Counsel’s responsibilities include assisting to narrow or resolve issues, directing parties to appropriate services and procedures, including dispute resolution processes, and providing guidance to parties, including discouraging unnecessary or inappropriate applications.

While there is potential for a “one family – one judge” model to be implemented in various court settings (i.e. unified family court, superior court, provincial courts), this may not be possible due to lack of resources or the realities of smaller centres. In addition, a downside of the “one family – one judge” model, is that in some cases it may involve delay for families, since they are waiting for “their” judge to be able to hear their matters. Alternatively, it has been suggested that other approaches such as a “one family – one team” approach could be used to promote consistency; the one team could, for example, comprise two judges as well as a case manager and a mediator.Footnote 238

The benefit in terms of coordination in family violence cases is as follows: a case that is carefully and consistently managed within the family justice system will be more easily coordinated with parallel cases in other sectors of the justice system.

5.2.3 One judge for all civil cases

One further step along the “one family – one judge” spectrum is exemplified by the State of Kentucky which adopts a “one family – one judge” approach with respect to its civil cases. This approach initially started as a pilot project in Louisville, Kentucky in 1991, and as of 2001 became a state-wide constitutionally established court. The central aspect of this approach is that all civil cases related to the same family are heard in the same court before the same judge; this includes matters such as divorce, custody, support, child protection and civil protection matters. While not all matters are heard on the same day, the single judge approach provides for consistency. While the civil judge does not hear criminal cases, there is a memorandum of understanding between the criminal and civil courts, providing that the criminal courts will generally defer to the civil courts with respect to “no-contact” provisions relating to family members.

A particularly important aspect of this system is the fact that each judge is supported by a court employee called a “case specialist.” The case specialist plays a very important function from the perspective of family violence. First, the case specialist is a neutral source for referrals to community services. Second, the case specialist is responsible for researching each case that comes before the judge to determine whether there are any related cases. The case specialist searches for both civil and criminal cases, and has access to all of the databases that would contain the criminal information. In this way, although the judge in the civil court is not making decisions related to the criminal case, coordination with criminal proceedings and orders is facilitated. The case law in the United States permits the courts to take judicial notice of prior court findings and orders (see subsection 6.1.5 in Chapter 6 for a discussion of judicial notice in the Canadian context). The case specialist is assisted in his or her search by the fact that litigants in civil cases are required to complete an intake form that asks for date of birth and their social security number and criminal accused are also required to provide this information. There are therefore common identifiers.

This search by the case specialist can be very informative to the court and sometimes to the parties. For example, in a hypothetical case, if parents are parties in a child protection case, the case specialist would be able to make known to the court and to the parties the existence of a previous child protection case involving the father and a different child and mother, in which the child was abused. This could have an impact on the disposition of the court in the matter. It may, however, also change the position of the mother, for example, if she did not know about the previous child protection proceeding and its outcome. As another example, where there is an application for a civil protection order, the search by the case specialist may help the court to better understand the context. In a case where a batterer is seeking a civil protection order against a victim, a search for previous orders could reveal that the batterer has been the subject of previous protection orders by different victims. This may, in combination with other evidence, lead the court to question whether a protection order is warranted in this case, or whether this is an attempt to use the legal system to control or harass the victim.

Another innovative aspect of the Kentucky approach is with respect to intake. When there is a report of family violence, there are several people present at the intake meeting with the alleged victim: a police officer, a prosecutor, a representative of victim services and a civil court clerk. Part of the intake meeting is a discussion about the coordination of different civil and criminal mechanisms, and this facilitates the prosecutor beginning criminal warrants while the civil court clerk can begin the process to obtain a civil protection order.

Coconino County in Arizona has an Integrated Family Court (IFC), which focuses on helping the family to achieve long-term solutions through a problem-solving approach. A pilot of the IFC was evaluated in 2008 which found that the court was successful in achieving its goals. The court has jurisdiction over all of the family’s related civil but not criminal issues, and adopts a “one family – one judge” model, with extensive associated specialized family services, including drug testing, anger management, domestic violence assessment and treatment, counselling, divorce education for children, parent education, supervised exchange, and both therapeutic and non-therapeutic supervised parenting time. Extensive assistance with respect to completing legal forms is provided to parties through self-help centres. In addition, the director of the Self-Help Center has direct access to the judicial assistant and the IFC judge, when necessary, to answer parties clarification questions with respect to orders and “next steps,” thus helping to expedite matters. Front end case management, and a focus on alternative dispute resolution are also key aspects of this model. Among the evaluation results, it was determined that the IFC had increased predictability, eliminated conflicting orders for families, and reduced the number of high-conflict cases.Footnote 239

5.2.4 One judge for civil and criminal cases – integrated domestic violence courts

Perhaps the fullest expression of the concept of “one family – one judge” is found with Integrated Domestic Violence (IDV) Courts. These have been established in a number of American jurisdictions, such as New York, Idaho, and Vermont, and there is now a pilot in Toronto, Ontario.Footnote 240 While the exact eligibility requirements and processes in the various IDV courts differ, they are united by some common principles: Footnote 241

- One family – one judge – One judge hears cases related to a single family on both the criminal and civil side.Footnote 242 As a result, this judge obtains a fuller picture of the situation and can make orders and decisions that are consistent and designed to address the family’s situation in its totality. Thus, orders with respect to matters such as bail, sentencing, protection or restraining orders, parenting (custody and access), orders to attend treatment (e.g. batterer/partner assault programs), as well as referrals to services can be consistent and comprehensive. Because one judge has a global picture, safety is enhanced. Further, there is an aim to increase the efficiency of the process for both litigants as well as the court system, with less court appearances and a quicker resolution of cases. Because one judge is dealing with all matters, it is also more difficult for family members to attempt to manipulate the justice system.

- Individual treatment of each case – While the same judge hears the family’s criminal and civil cases, all of the cases are treated separately and the rules of evidence and standard of proof associated with each process are applicable. Although the same judge is involved in both cases, supporters of the IDV Court model argue that it is integral to the judicial function to be able to hear evidence on one context, and then proceed to make findings without reference to that evidence, in another context. Courts do this on a regular basis when they make determinations about the admissibility of evidence.

- Coordinated resources for families – IDV courts generally have staff members who play a central role in acting as a liaison between the parties, the court and various community and other services. This resource person is generally responsible for helping to support adults and child victims by referring them to services, as well as helping an accused to access programs ordered by the court.

- Monitoring of compliance with orders – In order to improve offender accountability, IDV courts generally require frequent court appearances to determine if the offender is complying with conditions in orders, for example orders for no-contact, or to attend programs such as substance abuse or partner assault programs. In this way, offender accountability can be increased, because if there is non-compliance, the court can respond quickly.

- Victim advocacy – one of the key objectives of the courts is to improve victim safety and this is accomplished, in part, by ensuring greater consistency of orders. In addition, victim service providers often play an integral role in the court, by providing information, safety planning and access to services for victims.

- Involvement of community partners – IDV courts generally involve a great deal of collaboration with stakeholders such as police officers, probation officers, prosecutors, defence lawyers, family lawyers, victims services, partner assault program staff, services for children, lawyers for children as well as other service providers. There is recognition that IDV courts need to have support from stakeholders in order to function effectively, and thus ongoing communications and relationship building with stakeholders is generally viewed as important.

5.2.4.1 Toronto Integrated Domestic Violence Court

The Toronto Integrated Domestic Violence (IDV) Court was launched on June 10, 2011 on a pilot basis, and was developed, taking into account the research on IDV Courts and experiences of other jurisdictions. The IDV Court sits every other Friday. For a family to participate in the IDV Court there must be a criminal domestic violence charge originating out of two designated courts in TorontoFootnote 243 and a family court case in one of two of Toronto’s provincial courts.Footnote 244

The IDV Court will hear family cases involving any of: custody, access, child support, spousal support or restraining orders. Criminal cases are eligible when the criminal domestic violence charges have originated in the designated courthouse and the Crown is proceeding summarily. When a party approaches the court counter to file materials, staff may be prompted to ask about a criminal domestic violence case (e.g. if the party is asking for a restraining order). If it appears that there is a criminal domestic violence case, staff then provide the party with the IDV Court Information Package. A determination is then made as to whether there is a criminal case and if the matter is eligible for the IDV Court.

If a family case is already before the family court and the case is eligible to be transferred to the IDV Court, the family judge hearing the case must also consent to the transfer. A specific form has been developed for this purpose. If the family judge does not consent to the transfer of the case to the IDV Court, the cases will be returned to the regular family and criminal streams. If the judge consents, the cases will be scheduled into the IDV Court.

To prepare for the court appearance, the clerk ensures that both the criminal and family cases are on their respective dockets and the criminal information and family file are ready for the IDV Court judge. However, both the criminal and family matters will continue as separate files and the IDV Court judge hears each matter separately. Orders are prepared according to existing rules and practices. Staff in both the criminal and family courts make the appropriate data entries into the ICON (criminal) and FRANK (family) databases, throughout the process. Given that the Toronto IDV Court is a pilot, there are no new court rules. Existing court rules and procedures will continue to apply for criminal and family cases. For example, Crowns will prosecute according to Crown Policy and if eligible, individuals may be referred to the Partner Assault Response (PAR)Footnote 245 program in criminal domestic violence matters. Victims will continue to receive assistance from the Victim/Witness Assistance Program.

There are several services associated with the IDV court. For the first two years of the operation of the IDV Court, there was funding for a Community Resource Coordinator (CRC) who was present in the courtroom when the IDV judge was sitting. The CRC was responsible for:

- Connecting parties to community resources;

- Coordinating the transfer of clients to the IDV Court;

- Advising the parties of upcoming IDV Court attendances;

- Providing the judge with information and updates regarding the availability of community programs; and

- Reporting back to the IDV Court on the status of the parties’ court-ordered treatment.

In terms of legal services, on the day of IDV Court, Duty Counsel is available at the IDV Court to provide legal advice and assistance in court for family cases and the accused. The accused in the criminal case can also speak with Duty Counsel about their criminal matter. Other legal services available to the accused and the family litigants include: an Advice Lawyer at the Family Law Information Centres (FLIC), Legal Aid’s Family Law Service Centre, and Pro Bono Law students.

Since its inception, the IDV Court has had 31 cases on its docket (between June 2011 and August 2013). As outlined below, mandating eligible cases to the IDV Court (instead of requiring their consent) and adding the College Park criminal court to the catchment area of the pilot may also increase the number of cases before the IDV Court.

The IDV Court originally required the consent of all parties for a case to be transferred to the Court. As of winter 2011, very few cases had been transferred to the Court. Pursuant to a Practice Direction issued by the Ontario Court of Justice, effective March 16, 2012, cases are automatically transferred to the IDV Court, if the eligibility conditions are met. As a result of making attendance at the IDV Court mandatory, the IDV Court now hears trials of short duration and Crown consent is no longer required.

As of April 26, 2013, by Practice Direction issued by the Ontario Court of Justice, eligible criminal cases from a second criminal court – College Park – are included within the scope of the IDV Court. Adding the College Park criminal court to the catchment area of the pilot allows more families with concurrent criminal and family cases, to appear before the IDV Court.

Most recently, the Ministry has implemented the Family Court Support Worker Program (discussed further in Chapter 9), which provides support to victims of domestic violence who are involved in a family court process. The Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic currently provides the Family Court Support Worker services in the Toronto family courts, including at the IDV Court.

There are some potential challenges associated with the IDV courts in the Canadian context. For example, given that in Canada most criminal matters are heard in provincial court, there may be challenges associated with the IDV model for matters that must be heard at the superior court level, for example, proceedings under the Divorce Act or property matters; this may also be an issue in places where family matters are under the jurisdiction of a unified family court, which is a superior court. The Toronto IDV Court has addressed this particular challenge by limiting its mandate to include only family matters that may be heard by the provincial court. Another issue is that depending on the size of a court’s docket, particularly in less populated areas or smaller jurisdictions, there may be insufficient cases for a dedicated IDV court.

Concerns with respect to fairness and due process have also been raised in the context of IDV courts based on the perception that judges may be unduly influenced by evidence that they hear in one case affecting the family that is not admissible or before the court in the other case affecting the same family. Some have argued in response to such concerns that judges in this court model consider the merits of each case separately and decide each case based on the evidence presented and in accordance with the standard of proof required in that proceeding.Footnote 246 It has also been argued that judges regularly, in both criminal and civil courts, hear evidence which they find inadmissible, and then proceed to decide the case without reference to that evidence.Footnote 247 It therefore follows from these arguments that fairness and due process should not necessarily be compromised simply on the basis that the same judge is hearing both criminal and family cases. Also see subsection 6.1.5 in Chapter 6 for a discussion of judicial consideration of matters not placed on the record by the parties.

Despite these concerns, the Toronto IDV Court appears promising in approach and an evaluation of the benefits of the Toronto IDV Court by Professors Rachel Birnbaum, Nicholas Bala and Peter Jaffe is underway.

5.2.5 Judicial communications

Direct judicial communication involves discussion between judges where there are concurrent and related proceedings. The purpose of such communications is to coordinate each of the proceedings to ensure that they proceed more efficiently. The focus is not on the merits of the proceedings, but on the process that each is following. Judicial communications must be conducted in a manner which affords procedural fairness to all parties. In the absence of an IDV court, increased judicial communications between the various sectors of the justice system has the potential to improve coordination.

Direct judicial communications are increasingly being used in international cases. In Canada, they have primarily been used in the context of international child abduction cases.Footnote 248 There, judicial communications are used to obtain information about matters such as the custody laws of the other jurisdiction, to assist in managing the case in each jurisdiction more efficiently, and to promote return of the child, including by ensuring that mirror orders are made in each jurisdiction.Footnote 249

The Honourable Justice Donna Martinson has suggested that it could be possible to use this model of direct judicial communications in the context of simultaneous criminal and family law proceedings. The objective would be to provide for greater coordination and thus better outcomes for family members. She notes that in cases where there is no IDV court (the situation in most of Canada), the same objective can be achieved through judicial communications.

Case Study – An example of judicial communications in the family violence context

One example of communications between the Supreme Court and the Provincial Court took place in Kelowna, British Columbia in 2009. The issue was delay in the criminal proceeding. The Supreme Court was faced with an interim motion for custody by the mother, an order for no contact, and an order allowing her to leave the province. The father was accused of sexually interfering with a young child and faced a criminal trial in Provincial Court. The family was in chaos; this child and another were experiencing difficulties. Counsel advised the Court that because of the backlog in dealing with criminal cases in the Provincial Court, the trial could not be heard for many months, notwithstanding the important issues at stake.

The fact that the criminal proceedings were ongoing created significant problems in the family law proceeding. It was important that both proceedings be concluded in a timely way. The Supreme Court judge, with the agreement of counsel, contacted the local Administrative Judge of the Provincial Court to see if an early trial date could be obtained. The Administrative Judge immediately scheduled a case conference in her court to do just that. A timely trial date was obtained.

Excerpted from: The Honourable Justice Donna Martinson, “One Assault Allegation, Two Courts: Can we do a Better Job of Coordinating the Family and Criminal Proceedings”? Presented at the National Judicial Institute program, Quebec, November 2010 “Managing the Domestic Civil Case”

Justice Martinson suggests that another option would be for the two courts to hold a joint management/resolution conference in order to help manage both processes effectively. This same approach was suggested by Justice Glenn in Children’s Aid Society of Huron County v R G.Footnote 250 This could provide for a more consistent approach to safety and risk assessment as well as coordination of the processes. It may also provide an opportunity for all of those involved – judges, parties, and lawyers to discuss solutions that could work within the context of both the criminal and family systems. Such discussions would need to safeguard procedural justice guarantees. For example, in the criminal context the accused must be present whenever their case is discussed.

Where courts become aware of a simultaneous proceeding in another court, such judicial communications may offer a means to achieving better coordination in some cases.

5.2.6 Coordinated court/court coordinator models

Another model that has been recommended is a coordinated court model: the individual courts still specialize in family, criminal or child protection matters and these matters are heard by different judges, but the proceedings, evidence, and court-related services would be coordinated by a court coordinator.Footnote 251

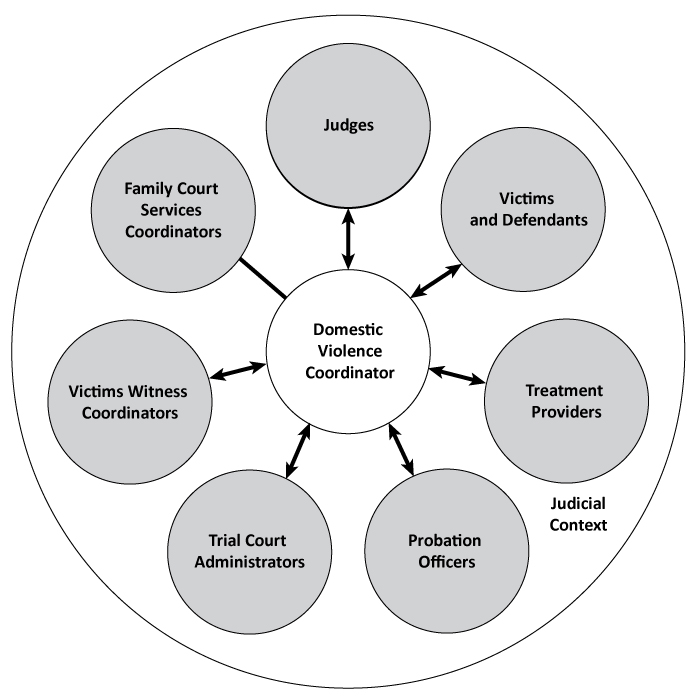

This approach is similar in concept to the role played by the Domestic Violence Court Coordinator in the Idaho IDV Court model. They are the center of the system linking the courts, services and family members. This model is illustratedFootnote 252 as follows:

Figure 3

Figure 3 - Text equivalent

This chart explains the central role played by Domestic Violence Coordinators in the judicial context. Their work includes interactions with: judges; Family Court Services coordinators; Victims/Witness Coordinators; Trial Court administrators; probation officers; treatment providers; victims and defendants.

While in the Idaho model the Coordinator plays this role within an IDV Court, conceivably, a Coordinator could play a similar role, although a more challenging one, by coordinating between the different justice systems, associated services and family members. In fact, although primarily focused on coordination in the criminal justice system, the Domestic Violence Court Coordinator in New Brunswick partially plays this role, through their information-sharing function between the different sectors of the justice system.

The Domestic Violence Division of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in Miami-Dade, Florida also has a model where administrative officers play a critical role in the coordination of cases and services. The Domestic Violence Court has jurisdiction over civil injunctions, orders of protection, violations of orders and misdemeanor criminal offences involving domestic violence. The court also has jurisdiction over all family law issues, including division of property, custody and support. There are seven judges of the court who rotate in and out of hearing the civil and criminal cases. Unlike the models in New York, Idaho and Vermont, there is not a “one family – one judge” model. Coordination, however, is facilitated through “intake officers” and “case managers.”

In the Miami-Dade model, there is an intake unit, which provides assistance in obtaining temporary injunctions (protective orders) as well as referrals to community resources. The intake process uses what is described as a “customized state-of-the-art network and client-server software application program”, which allows all case information to be available to the Clerk of the Court, for follow-up and reprinting of forms as necessary. Once a case is processed, the network database searches for all pending or connected civil, family, juvenile and misdemeanor criminal court cases. This information is included in the petition for the injunction with the purpose of avoiding conflicting orders.

The case management unit is staffed with lawyers, and their primary role is to help the Domestic Violence Division with respect to permanent injunctions (permanent protection order) hearings. Their role is particularly important since most litigants are unrepresented. The case managers have numerous functions, which include to:

- Provide information to litigants about the court processes and community resources;

- Cross reference information between the Domestic Violence, Family, Criminal and Juvenile divisions of the Court – to ensure a coordinated approach and reduce the likelihood of conflicting orders;

- Write draft orders for the court on issues such as visitation schedules;

- Calculate child support;

- Make referrals to community agencies providing services;

- Conduct criminal and injunction checks, in advance of a determination of whether referral to a 26 week batterer’s intervention program is appropriate (it is mandatory in some cases and if an individual has had a previous injunction in any jurisdiction, there is a mandatory requirement that they attend a batterer intervention program); and

- Monitor compliance with the conditions of injunctions.Footnote 253

Although there has been no formal evaluation of the Domestic Violence Division, Judge Kelly, the Administrative Judge of the Domestic Violence Division, reports that it is working well. Further improvements to the functioning of the court, including the ability to search additional criminal databases are under consideration.

5.2.7 Aboriginal Courtwork Program

The Aboriginal Courtwork (ACW) Program serves as an example of a service that can assist with respect to the coordination of the different court sectors. The ACW's primary purpose is to help Aboriginal people who are in conflict with the criminal justice system to obtain fair, just, equitable and culturally sensitive treatment. This objective is achieved by:

- Providing non-legal advice and information to Aboriginal persons charged with an offence and their family members at the earliest possible stage and throughout the criminal justice process;

- Referring Aboriginal persons charged with an offence to appropriate legal resources at key stages of the justice process (e.g. arrest, trial, sentencing);

- Referring Aboriginal persons charged with an offence to appropriate community resources, including alcohol, drug and family counselling, and educational, employment and medical services to ensure they have help addressing the underlying problems that have contributed to their criminal behaviour or problems that have led to the laying of criminal charges, and where appropriate, advocating for services for Aboriginal persons charged with an offence and ensuring that those services are delivered;

- Providing assistance, as appropriate, to other Aboriginal persons involved in the criminal justice process (e.g. victims, witnesses);

- Promoting practical, community-based justice initiatives and helping build the capacity of these programs to identify and address problems that could end up in the courts or community justice system;

- Serving as a bridge between criminal justice officials and Aboriginal people and communities, by providing a liaison function and facilitating communication and promoting understanding between the parties; and

- As “Friends of the Court,” providing critical background and contextual information on the accused and making the court aware of alternative measures and options available in the Aboriginal community.

In many jurisdictions, there are no Aboriginal-specific services providing information, support and referrals for family law court cases; therefore jurisdictions report a need to better connect criminal and family justice system responses. Many ACW Programs report that they are often asked to continue to support their clients through parallel or related proceedings in family law or child protection matters.Footnote 254

ACW family law services do exist in some jurisdictions. Alberta and Ontario have been supporting ACW family services for over 35 years and Saskatchewan is currently piloting ACW family services. In the Northwest Territories, the role of ACW services in family matters expanded following a study in 2008/2009 that provided recommendations on how courtworkers could provide additional services to family law clients. Where they exist, ACW family law services allow for services similar to those provided to clients with criminal matters: information, support, liaison and referral services to Aboriginal parents and other family members in relation to family law or child protection matters, and establishing effective communication between Aboriginal people and justice officials.

- Date modified: